The problem is the SOILution | An interview with Sasha Kramer

Photo by The Moon Magazine

Originally published on The Moon Magazine

Sasha Kramer is a slight, blonde former New Yorker who got a Ph.D. in ecology from Stanford University in 2006, the same year she co-founded SOIL (Sustainable Organic Integrated Livelihoods)—a nonprofit headquartered in Port-Au-Prince, Haiti. SOIL’s mission is to “promote dignity, health, and sustainable livelihoods through the transformation of wastes into resources.” In other words, composting human wastes to create the rich, black soil that Haiti desperately needs, while eliminating the pathogens and pollution the country doesn’t need. SOIL doesn’t intend to do this for Haitians, but to support them in undertaking this work—as a profitable, self-sustaining enterprise for themselves, or as a model that can be implemented by their government.

Kramer’s work has been honored with many awards, including an Ashoka Changemaker Award, a National Geographic Emerging Explorer Award, a Schwab Foundation Social Entrepreneur of the Year Award, and a Land for Life Award from the United Nations’ Convention to Combat Desertification. SOIL has also been written up in the New York Times, National Geographic, The Guardian, the Huffington Post, Sierra, the BBC, Forbes, and dozens of other publications.

Kramer lives and works in Port-Au-Prince, but travels extensively as a global advocate for the recycling of nutrients in human waste and inspiring people to participate in a “global sanitation revolution.” She recently returned to the States from a conference in Vietnam and spoke with The MOON by phone from New York.

The MOON: How did you come to create SOIL?

Kramer: I was a graduate student in ecology at Stanford University when I read The Eyes of the Heart: Seeking a Path for the Poor in the Age of Globalization, by Jean-Bertrand Aristide, Haiti’s first democratically elected president. The book had a huge impact on me, making me wonder how I might use my ecological training in a way that would also advance human rights. When Aristide was overthrown in a military coup in 2004 I accompanied a group of human rights observers to assess conditions in Haiti. I spent three weeks in northern Haiti attending demonstrations, visiting political prisoners, and falling in love with the country and its people.

I went back another dozen times and realized that the most pervasive human rights abuse in Haiti was—and remains—poverty. People don’t have the means to get their most basic human needs met. In 2000, when Aristide’s book was published, one percent of the Haitian population controlled 45 percent of the country’s wealth. Eighty-five percent of the population could not read and write. And more than half-a-million children, mostly young girls, lived in Haitian households as unpaid domestic workers — carrying water, cleaning house, doing errands, receiving no salary and no schooling. That was fifteen years ago, and for many and the situation has gotten even worse since the earthquake that demolished Haiti in 2010. One of the most basic needs Haitians don’t have access to is sanitation.

I’d never even thought about it before; I’d never had to. But in Haiti’s rural areas only 16 percent of people have access to toilets, in cities only 35 percent. This is the lowest sanitation coverage in the Western Hemisphere. People dispose of their wastes in the ocean, rivers, plastic bags, and abandoned lots. In many places, there is nowhere to go to the bathroom privately.

This isn’t unique to Haiti. According to the World Health Organization, 2.5 billion people don’t have access to any kind of improved sanitation; one billion practice open defecation. More people have a mobile phone than have a toilet. I’d heard of compost toilets and ecological sanitation, so it seemed like a great way to bring together concern for human rights and my ecological education: a way to promote the basic right of sanitation through an ecological approach.

I started talking with the community organizers I’d been working with and people got really excited about the idea. They’d already been thinking about sanitation—for reasons of privacy, security, and disease control—and the potential to produce compost from human waste was another inducement, adding value for Haiti’s farmers. So together with an amazing group of Haitian community organizers and a brilliant engineer from the United States, I co-founded Sustainable Organic Integrated Livelihoods (SOIL) to “promote dignity, health, and sustainable livelihoods through the transformation of wastes into resources” in 2006.

SOIL is based on a philosophy we call Liberation Ecology, which recognizes that the most threatened and marginalized human beings are generally found living in similarly threatened ecosystems. Our goal is to empower people in Haiti to restore their environments by transforming dangerous pollutants into valuable resources.

The MOON: How did you happen to pursue ecology when you were so passionate about human rights?

That’s a good question. I have a scientific mind, but still, I went back and forth. When I was very young I wanted to be a doctor and help people. Then I went to Reed College, in Oregon, and got involved in the environmental movement and thought, “People are the problem! I’m going to do environmental work!”

Then I guess I grew up a little bit and thought “There must be a way to bring people and the environment together.” Ecology seemed the way to do that. Plus, I’ve never been cut out for the social sciences, even though I’m passionate about social issues.

The MOON: Is it true SOIL provided Haiti’s first waste treatment plant…in 2009?!

Kramer: That is true. Prior to 2009 there was no waste treatment in Haiti. In 2009, SOIL built its first composting site, which was also the first formal waste treatment site in the country. The government built its first waste treatment site in 2011 and has since built two more, but two of the sites are not functioning. So there is only one functioning government waste treatment sites in all of Haiti—a country of 10.3 million people. On a brighter note, SOIL’s composting sites in the capital and the northern city of Cap-Haitien are safely transforming tons of waste each month and there are also some smaller-scale composting and waste-treatment sites cropping up around the country. The government sanitation authority (DINEPA), also has an ambitious plan for scaling up waste treatment around the country in the next decade, hopefully integrating some of SOIL’s composting technologies.

So most of the country’s waste goes untreated. Most of those with flush toilets use septic tanks, but they are so closely packed together that there’s really not sufficient treatment going on. The septic tanks are leaking contents with untreated pathogens, typically downhill into poorer neighborhoods, or into the canals, rivers and eventually the ocean. And those who have latrines generally pay someone from the informal sector to empty the latrine into a nearby pit or body of water.

The MOON: Joe Jenkins mentioned he’s been working with Give Love, a nonprofit started by Patricia Arquette, which has done a village-sized compost site.

Kramer: Yes, we’ve seen their facility and it’s quite amazing. However, although our systems are in many ways similar and based on the same philosophy and processes, Give Love’s facility is in a rural area where there is space available for composting on-site, lowering their costs. SOIL works in dense urban areas where there is no space for composting; hence the need for an offsite composting facility. But having these two examples provides an excellent foundation for comparative research and sharing of lessons learned, so we are pleased to have a collaborative relationship with Give Love.

The MOON: How much waste are you treating at your two facilities?

Kramer: We’re treating around 25,000 gallons of waste a month—which translates as the poop of about 4,000 people. This is down from about 22,000 people at the height of our earthquake response. People have been moving out of the emergency camps into permanent housing, so our supply of poop has dropped. Our composting sites are in Cap-Haitien, the second-largest city after Port-Au-Prince, and in Truitier—which is the site of the city dump for Port-Au-Prince, the Haitian capital. The dump is actually quite a horrible site, from an ecological perspective, with a lot of burning trash, odors, flies, rats, and other pests. It makes quite a contrast with our clean, odorless compost facility.

Although the location is undesirable from an aesthetic standpoint, it relieves the anxiety people have about poop treatment in their neighborhood—especially since the cholera epidemic.

The MOON: But isn’t poop treatment the solution, not the problem, to cholera epidemics?

Kramer: It absolutely is; but nonetheless, we try to be sensitive to people’s concerns. So it’s good to have our facility in a location that people can visit easily, but where the community has accepted it.

The MOON: And now you have a Poopmobile and an experimental farm at Penye?

———————————————————–

Part 2:

Originally published on The Moon Magazine

Kramer: Yes. We actually have a couple of Poopmobiles because, as the majority of our toilets are in very, very dense urban areas, the poop has to be collected and transported to the compost site. We have a team of collection workers that goes door-to-door on a weekly, or biweekly, basis and picks up the full buckets and delivers clean buckets, which also contain the carbon material that is the other key ingredient to making compost. In many neighborhoods the streets are so narrow that a truck can’t negotiate them, so the workers use wheelbarrows to get buckets to and from the Poopmobile—which transports the poop to the compost site. After the poop is composted, it can be sold to farmers, businesses, and institutions around the country to subsidize the cost of SOIL’s waste treatment operations. To date we’ve sold over 75,000 gallons of EcoSan compost—and we’re actually selling more than we’re producing, since our poop supply has dropped. However, it takes about a year for the poop to compost, so we are still able to meet demand, based on previous years’ collections.

When we’ve had excess compost, we’ve applied it to our experimental farm at Penye, which serves our Port-Au-Prince site. We also have a test farm at Cap-Haitien. At both sites we test the performance of the compost on different crops.

The MOON: But doesn’t the compost benefit all crops?

Kramer: Yes, but compost is relatively expensive to produce—even in the U.S. It will boost the production of any crop, but we want to be able to advise poor farmers on the crops that it would make the most economic sense for them to use it on. If it’s a low-value crop, like corn or beans, maybe not; if it’s a high-value crop like spinach or peppers, a farmer would get sufficient yield increases to pay back his or her investment. Over the long-term, using compost will rebuild Haiti’s soil, so it would be wonderful if everyone could use it. Poor farmers might not have that luxury, but backyard gardeners, landscapers, and others can. And of course, the sale of compost helps support our sanitation operations.

Haiti’s problem isn’t lack of soil fertility, but lack of soil itself. Deforestation has eroded whole layers of soil, which runs into the ocean every year. High-altitude photos show a brown ring of soil and human waste runoff hugging the coastline. Ecological sanitation gets that out of the water and back onto farmland to enrich, not pollute. Haiti’s soil is so thin, even massive amounts of chemical fertilizers can’t restore soil structure. On the other hand, fertilizer from human waste provides nutrients and carbon essential to rebuilding soil. Producing a resource themselves that will make Haitians less dependent on other countries really excites and motivates them. Although their dignity is challenged in so many ways, they have tremendous national pride and desire for self-sufficiency.

The MOON: And what cover material—what carbon ingredient—is SOIL using—bagasse?

Kramer: Yes, we use bagasse—the fibrous remains of sugar cane after processing—just like Joe Jenkins and Give Love are doing, but we also have a great supply of ground-up peanut shells, because there’s a lot of peanut butter processing in Haiti. These make an excellent cover material. We’re actually mixing the two—the sugar cane bagasse and ground peanut shells. We call that “Bonzode,” which means “good smell” in Haitian Kreyol.

The MOON: Tell us about the SOIL business model.

Kramer: When we first started SOIL we thought we’d build thousands of toilets every year and get sanitation to as many people as we could. But as we spent more time here, we started gaining an appreciation for the ways in which projects led by international NGOs are generally not sustainable in the long run. We decided that it really wasn’t the place for an international NGO to be providing sanitation for Haiti. It would be better if we provided some research and development and the Haitians took over providing sanitation for themselves.

Now we’re working to develop small business models for the communities in which we provide toilets. The model we’re currently testing involves renting the toilets to our customers for a fee of approximately $5 U.S. a month, which covers the cost of poop collection and cover material provision. We have about 300 paying customers in Cap-Haitien. We’re testing this model here to ensure that a private entrepreneur could actually make a profitable business from it. If so, we’ll train individuals to become those private business owners. That would become our method of scaling up, as well. Private business owners would do the outreach to expand their customer base and create a sustainable business for themselves and sanitation for urban areas in Haiti.

So far it’s going pretty well, although not without challenges. We worked up to the rental payment model very gradually, and fully implemented it to these 300 households in 2013. However, it appears that the break-even point would be about 500 households, and we’re not there yet.

The whole model represents quite a cultural shift in Haiti, where people rarely pay for utilities. There’s certainly no history of paying for sanitation. People either get whatever services they have for free or they don’t have them. Although people are very happy with the toilets and they’re happy with the service, collecting payment is difficult. The workers have to visit the house once a month and hope that the customer is home and has the money. If not, they have to come back. It’s a very time-intensive process. We’re researching mobile phone payments—but here again, that technology hasn’t yet taken off in Haiti, though it would make payment collection much easier.

The MOON: It’s been fifteen years, but I’ve spent quite a bit of time in poor communities in the Dominican Republic, Haiti’s neighbor, and people don’t have checking accounts or use financial services there. If you have to make a payment, you take cash, or you send it via Western Union or some other money-transfer service.

Kramer: Right. So there’s no automatic credit card payment option either.

The MOON: Who builds the toilets?

Kramer: That’s one part of the process we have been able to hand over to the private sector. We trained about ten local carpenters to build the toilets. Whenever we have an order, we put out a bid and contract with one of the carpenters. That’s been great because the carpenters have suggested innovations and improvements within the parameters we gave them: a box that can hold a five-gallon bucket, a seat, or lid, and a cost of less than $50 U.S. They’ve come up with improvements that customers like even better than our original design.

The MOON: What difference would you say SOIL is making in Haiti?

Kramer: The short-term difference we’re making right now is with the seventy Haitians employed by SOIL and our 4,000 customers. Most of our employees have been with us for years. It’s their passion and enthusiasm that’s really responsible for SOIL’s success in the larger community. Many of them use our toilets in their own homes; everyone is excited about the food and other crops they grow with our compost; and they love that, by tackling one problem, the solution also benefits public health and the growing of food and other crops. Because compost takes a year to mature, the first year of operation we couldn’t harvest any; we just had to trust that what we were doing would work; would make beautiful soil. But when we harvested our first compost and actually got that soil, it was a real turning point for all of us. We became excited about the transformative power of ecological sanitation.

In the long run the difference SOIL could make would be in business ownership possibilities that people could be proud of: a business that is cleaning up the environment, protecting public health, and helping to rebuild Haiti’s soil. A successful business model would, in turn, trigger the scaling up of the process so that sanitation could reach more of Haiti’s people.

The MOON: I would think that the employees would also be excited about the dignity of having a toilet to use in the privacy of your own home; the convenience of not having to go to a public toilet; the luxury of a toilet that doesn’t stink. It seems that there are a lot of daily, practical advantages to be excited about, as well.

Kramer: Absolutely. That’s clearly what motivates our customers. It’s about having a toilet in their own home; about not having to go out—particularly at night, particularly if you’re a child or a woman—to use a toilet; about having a toilet you can offer your guest. Toilets offer dignity, security, cleanliness, comfort and convenience.

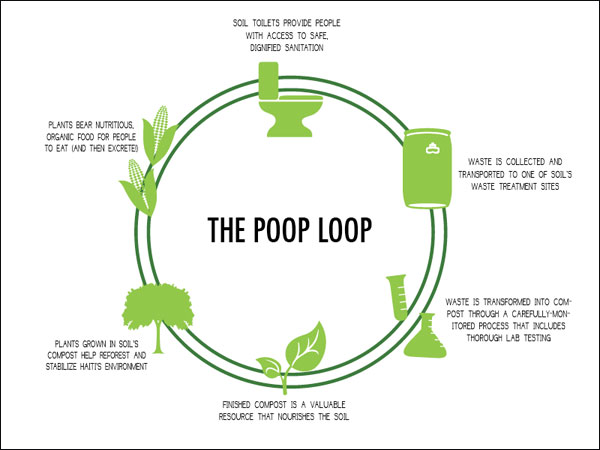

Because we do a lot of education around the full-cycle nature of the whole composting business—the Poop Loop, we call it—there are some customers who share our enthusiasm about the public health and soil fertility benefits, but their immediate motivations are more personal. Once your basic needs are met, you can expand your care and concern to the environment; until then, you just want your basic needs met.

The MOON: What is your vision for SOIL?

Kramer: That SOIL will get out of the toilet-building business, having started a movement that will provide sanitation services on a large scale for Haiti. And the success in Haiti will serve as a model for providing sanitation services in poor, dense, urban environments in other parts of the world.